Dr Alice Miller is a medical doctor and PhD student in public health at the University of Otago. She and her colleagues recently published the paper: The road lobby and unhealthy transport policy discourse in Aotearoa New Zealand: A framing analysis. LSA interviewed Alice to learn more about this research and how advocacy organisations can respond to the road lobby.

The long-form interview, lightly edited for clarity, follows.

Photo: Dr Alice Miller, PhD student at University of Otago (photo supplied)

Can you tell us a little about your background and how you came to do this research?

I'm a medical doctor, and I worked for about 10 years as a GP, and have recently moved into public health, and I am interested in researching transport in relation to health and in relation to climate change. And all those things are really interlinked.

What is the “road lobby”?

So we looked at a cross section of trade associations from across the road transport sector, and we included organisations that represent the car industry, businesses related to the automotive industry, the road freight sector, those sorts of organisations. And out of those ones that we looked at, we identified a number that were lobbying for road transport and largely finding all sorts of reasons that New Zealand couldn't or shouldn't do active transport or public transport improvements. So yeah, there were large, well resourced commercial organisations that were undertaking a range of political activities to try and influence transport policies in the interests of their industry members.

For this paper, your team analysed submissions that the road lobby made on government policy. What kind of policies does the road lobby submit on?

So we took a sample of policy consultations from recent years, transport policy and climate policy that was related to transport, and so we didn't analyze all their submissions that they made across every policy, but we looked at a sample of those. And we analyzed those policy submissions in quite a lot of detail, looking at the policy positions that they took and also how they argued for or against different policies, particularly looking at the way that they framed problems and solutions, like who's responsible for different transport issues, who's responsible for solving those issues,and how we should go about that.

What were the main results of this research?

So one of the main things I've mentioned already is that we did identify a number of large, well resourced organisations who are actively out there trying to influence government policy on transport, and they had incomes ranging from sort of hundreds of thousands of dollars to hundreds of millions.

And what we found is that those road lobby organisations argued for policies that promote driving and taking freight on trucks, and at the same time, they either opposed or gave lots of reasons why we shouldn't or couldn't implement policies that would improve active transport and public transport. So, for example, things like reallocating road space from vehicle lanes to provide safe areas for people to walk and cycle, reallocating some of that transport revenue from roads into different modes of transport, and also things like reducing vehicle emissions that would make the air cleaner for us to breathe. Those sorts of pro-public health transport policies were sometimes outright opposed, but often there was kind of a lot of doubt raised about the effectiveness of the policy, or there was a desire to delay it, and all sorts of arguments given as to why it wouldn't be possible or it wouldn't be a good idea to do that.

What kinds of arguments do organisations make in these submissions?

Yeah, so we saw a lot of similarities with the types of arguments that were used, as we see other industries doing when they want to resist a policy that doesn't suit their interests. So, for example, the tobacco industry is a key example of this. They have a range of framing strategies and the way that they spin things to try and convince the public and to try and convince government that passing a law isn't a good idea. And we found an awful lot of similarities to what other researchers have found across those harmful industries.

One example is that there's a lot of emphasis on people taking individual responsibility for the emissions of their transport choices. And we see that commonly across harmful industries that they say: “Oh no, we shouldn't regulate this. People should just take responsibility for their own choices as a consumer.” But what was interesting and was in the submissions that there was still very much an acknowledgement that, well, people don't actually have a reasonable choice in many cases, but to drive, because we don't have a good enough safe infrastructure, safe places for people to walk and cycle, and we don't have frequent, affordable public transport in lots of places. So yeah, we found that was a particularly interesting argument.

And one of the other arguments that tends to come up from industries is there was this repeated advocacy against the government taking an active role in the transport sector through regulation or through investment or subsidies, unless it involved building roads or subsidizing things like EV infrastructure. So yeah, that was quite a striking finding that we had there.

One main priority of Living Streets Aotearoa is improving pedestrian safety. So what were their arguments around road safety in particular?

Yeah that was another interesting thing that we found was that the organisations often use the concept of road safety to back up their arguments for more spending on roads and motorways. And, of course, it is important for us to maintain our existing roads well, and that is one element of road safety. But there are many, many other ways that we can improve road safety. Of course, we can reduce the number of vehicles on the road by encouraging people out of their cars and into other forms of transport that then make our streets safer.

But also we felt that they were really distracting from the harms caused by vehicles themselves, by the products and services of those industries. And also the way that road safety was discussed was in a really narrow sense. It sort of referred to injuries and and deaths from crashes, but it ignored other really major health harms from the transport system, like physical inactivity, like air pollution, like climate change, and sort of just diverted thinking towards the idea that we need to upgrade the roads to make them safer, and those other things were really not discussed.

And it's a tricky kind of argument, because it's easy to fall into that trap. But, of course, it is much safer on the roads if you make your cities with multi-modal transport options, with safe places for walking, with safe places for people to cycle or use buses and trains, because then we actually reduce the speeds, reduce the number of cars on the road.

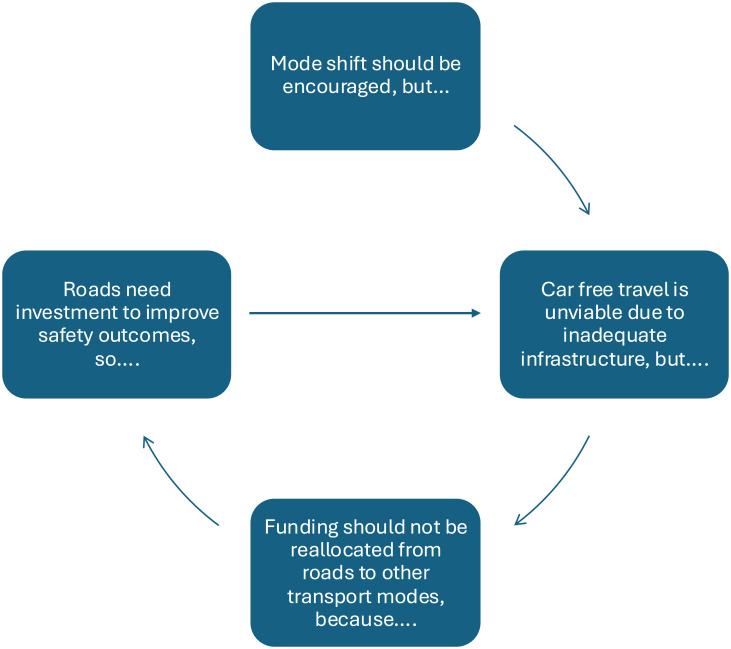

There was a great diagram (see below) in your paper explaining how these arguments about road safety are circular. Could you describe this diagram and what it means?

So that was really something that popped out as I was doing the analysis, which was that when you take the arguments all together, you get this kind of dead-end argument. There was a bit of support in some of the wording: “Well, yeah, we kind of agree that people should walk and cycle more, but people can't, because the car is their only option, because we don't really have any other alternatives.” But then at the same time, we get the argument: “Well, we shouldn't reallocate any funding or any space from cars and trucks to other forms of transport, because we need to spend that money on the roads to make them safe.” So we found it really interesting how when you follow those common sorts of threads through, it sort of locks us into this status quo, which is people just have to keep driving because there isn't any alternative to driving, which, of course, is a completely false argument.

Fig. 1 Circular argument blocking investment into mode shift by Miller et al from "The road lobby and unhealthy transport policy discourse in Aotearoa New Zealand: A framing analysis."

Published in the Journal of Transport & Health. Licence CC BY-NC 4.0

How might the road lobby influence transport policy and infrastructure in New Zealand?

So I think we can only mainly comment on what we researched, which was looking at the submissions. And from this research, we can't say: “Well, you know, these submissions or these arguments actually materially affected the outcomes.” But what we can say is that there are a bunch of well resourced organisations out there who are arguing against policy that would get people walking or would make our streets safer for people who are not driving cars. So we think this is a good piece of research that shows more light needs to be shined on that.

For example, we know that from publicly available information, some of these organisations do have active working relationships with government agencies like the AA, for example, they provide driver licensing services and do all sorts of other things. And they claim in their public facing material that they have ongoing relationships with government departments and agencies and things like that. So we think that more questions need to be asked about exactly what role they have in the policy making process. And is that being balanced against other voices from the community, including sustainable transport advocates groups like Living Streets Aotearoa, climate advocates, community groups. And I think one observation that we made after we completed our research was that there was a lot of similarity in what we found here, in these submissions, and the way that it was argued for with the most recent government policy statement on transport. And we just found that was quite striking.

What can LSA and other advocacy groups do to deal with the power and influence of the road lobby?

I think as with any problem, the first step to do is to acknowledge that there is potentially a problem. And I think that our piece of research hopefully gets people thinking about this in a different way, so that as advocates we can be saying: “Look, we are advocating for policy makers to actually consider the vested interests of all the stakeholders that they're interacting with, and we would like you to make sure that your decision making and processes really actually give enough weight to health and to environmental outcomes.” So we can be pushing and asking questions.

But also in the paper, we do give some advice for how to go about countering some of the arguments. And there's some really good resources out there around how advocates can frame messages to make them effective. One example that we give is giving a new kind of “virtuous circle”, instead of that circular policy block, which just really emphasizes the evidence that shows that when you do invest in walking infrastructure and in cycling infrastructure and fast, frequent public transport, that you see people using it, and then that drives more people to use it, and that drives more investment. And then the co-benefits associated with that are huge. So you get the health co-benefits, you get economic co-benefits, you get environmental co-benefits. You make your cities more livable and nicer places to live. So it's not different to what is being done already, but it just emphasizes that there are these other narratives out there and that it works to repeat that positive framing. It's really important to carry on emphasizing that over and over again in a way that's understandable for people.

Are there areas where pedestrian advocates can either learn from the road lobby's tactics?

I think it is generally good to keep framing positive, but at the same time, I don't think it's wrong to highlight power imbalances. And anticipating the arguments that will come can be really useful, because in your messaging, you can sort of pre-bunk them, like you can prepare your response with some of your evidence or your research base, or your experience, or what have you. If you know some of these arguments that are likely to come, then you can come back with counters before they've even started.

Are there any ways LSA and other advocacy groups can get the road lobby alongside us?

I think that speaks to the point of alliances and alliances being potentially really useful. And we definitely did find that some organisations have a lot more nuance in their arguments than others. For example, the Bus and Coach Association were quite interesting. We didn't categorize them as part of the road lobby as such, because they were much more supportive of active and public transport modes. So we question whether that could be an alliance that could be worth exploring, because some of those agendas are quite similar like environmental benefits, reduced congestion, having adequate road space for different modes.

Do you have further research that you're working on, or ideas of where to take this research next?

Yes, actually, I am now doing a PhD, which is along similar lines, and I'm looking a bit more broadly at the transport policy network as a whole. So not just commercial interest groups, but the whole range of people and organisations involved in transport policy and trying to find out about where influence is situated and where power is situated, and what strategies are used by different individuals and different groups to try and influence transport policy. And the hope is that we'll be able to tease out some of these questions about how we make our transport policy decision processes, or how we can make sure that they are balanced and they are reflecting a range of voices and taking into consideration a range of positive outcomes as well as the harmful externalities of transport.

I think the challenge is that we're trying to change the direction from a direction that it's been in for a long time, and there are various factors that tend to hold the status quo in place. So hopefully we'll be able to just dig into that a little bit more, and see some more positive progress on on our multimodal transport, because it's so obvious from other countries and other cities around the world, and also from progress that has been made here in Wellington and Christchurch and Auckland, that it just works better. Yes, you get the health you get the health benefits, you get the emissions reduction, you get the air quality benefits, but people who need to drive can also get where they want to go more easily because there's less traffic, and people that live in those cities have nicer spaces to to live in, and people feel safer walking around and just going about their daily life, so we know it's the right thing to do.

Do you have anything else to add?

Yes I think it’s important to talk about more of the intersections between transport and public health. For example, the annual social costs of the health impacts and vehicle pollution is estimated at $10.5 billion per year in New Zealand. And the air pollution from motor vehicles causes thousands of hospital admissions a year from asthma and from heart conditions. We think about crashes and deaths, which are tragic, but air pollution is invisible. I think lots of people don't think about it, or are even aware of it. This is a major burden on our hospitals and on our medical system, which is groaning under the strain at the moment, and it is absolutely preventable by shifting the way that we travel.

And it's not rocket science or new technology that hasn't been invented. It's stuff that is out there and that we also know that lots of people would choose to travel in a different way if they had the option to hop out of their car. When I was a GP, and this is why I came into doing this work, every single day I was seeing people who had preventable illnesses–diabetes, respiratory conditions, heart conditions, arthritis, mental health conditions that actually would have been avoidable if they were regularly physically active. So yeah, I think joining some of those dots and getting people to think about the ways that we could prevent pressure on the health system and increase active transport is a huge part of it.

Alice was also recently interviewed by RNZ.